Let's start a bit further back in history, because this story is mostly about, of all things, aerial surveillance and military intelligence. The 1940's ended with the Soviet Union exploding an atomic bomb, which took the United States and the rest of the world pretty much by surprise. The newly-elected President of 1953, Dwight Eisenhower, made it a top priority that the US government would no longer tolerate "surprises" in military intelligence. Ike demanded a clear picture of what the Soviets were up to: what their A-bomb inventory was, how many long-range bombers they had, that kind of thing. Congress, also appalled by the lack of strategic information, agreeed. Of course, this kind of information would require some sort of sophisticated aerial reconnaissance.

One of the most difficult problems in surveillance of another country by a military aircraft was that the act of overflight would, at least in the early 1950s, be considered an overt act of war. Sending USAF planes over the USSR would be the perfect trigger for the world's first nuclear exchange.

Eisenhower tried a radical diplomatic step to deflate the concerns about Soviet missile and bomber counting flights: he suggested that all nations adopt an “Open Skies" policy, where overflights by surveillance aircraft from other countries would be permitted over national boundaries. The Soviets rejected the proposal immediately, so Eisenhower was forced to come up with a sneakier way of taking pictures of Soviet airfields.

In 1955, Ike asked Dr. Edwin Land (yes, the Polaroid guy) to put together an intelligence subcommittee for the "President's Technological Capabilities Panel." This group would scope out any wacky, harebrained plots thought up by American scientists and engineers to reduce the provocative nature of the overflights. Land came up with an idea that the designs for a canceled Air Force spy plane, the CL-282, be transferred to the civilian Central Intelligence Agency. Land convinced Eisenhower that the civilian Central Intelligence Agency, and not the United States Air Force, would provide pilots and operational support for any overflight missions, thus pre-empting the potentially catastrophic shoot-down of a military aircraft with a military pilot on-board. The CIA would then be in charge of reconnaissance operations with this new craft, renamed U-2, and civilian pilots would fly these spy planes on high-flying missions through Soviet airspace. With a fat, secret Congressional budget, the CIA built a handful of U-2 planes inside of a year.

| |

| Dr. Land's airplane: the U-2. |

Only ten days after the U-2 plane became operational in mid-1956, President Eisenhower ordered the overflights to cease. Signal intercepts of Soviet radar stations indicated that the USSR was aware of the flights, and Eisenhower did not want to risk a shoot-down incident. Despite only flying a week and a half, the U-2 planes gave lots of tantalizing bits of information about airfields deep in the Soviet heartland. Ike needed another alternative to the U-2.

An obvious answer was a satellite, but Eisenhower still worried about the overflight by a spaceship (even one in orbit) as being an act of war. True, the flight would be unmanned, but the government division launching the rocket would be the US Army, led by an ex-Nazi rocket scientist with dirty hands.

Wernher von Braun, the Army's chief rocket designer, had quite a tainted past. He didn't begin his rocket career as a Nazi, but he certainly excelled in his craft during his tenure with them.

Amateur rocket societies flourished in Germany during the 1920’s and 1930’s, the largest of which was Verein für Raumschiffahrt (Society for Space Travel), or VfR. The rocket societies were not created for military research, but were social organizations for like-minded individuals who were interested in the exploration of space and the increase in scientific knowledge. Key German scientists and authors such as Hermann Oberth, Willy Ley, and Max Valier were early members --- so was von Braun.

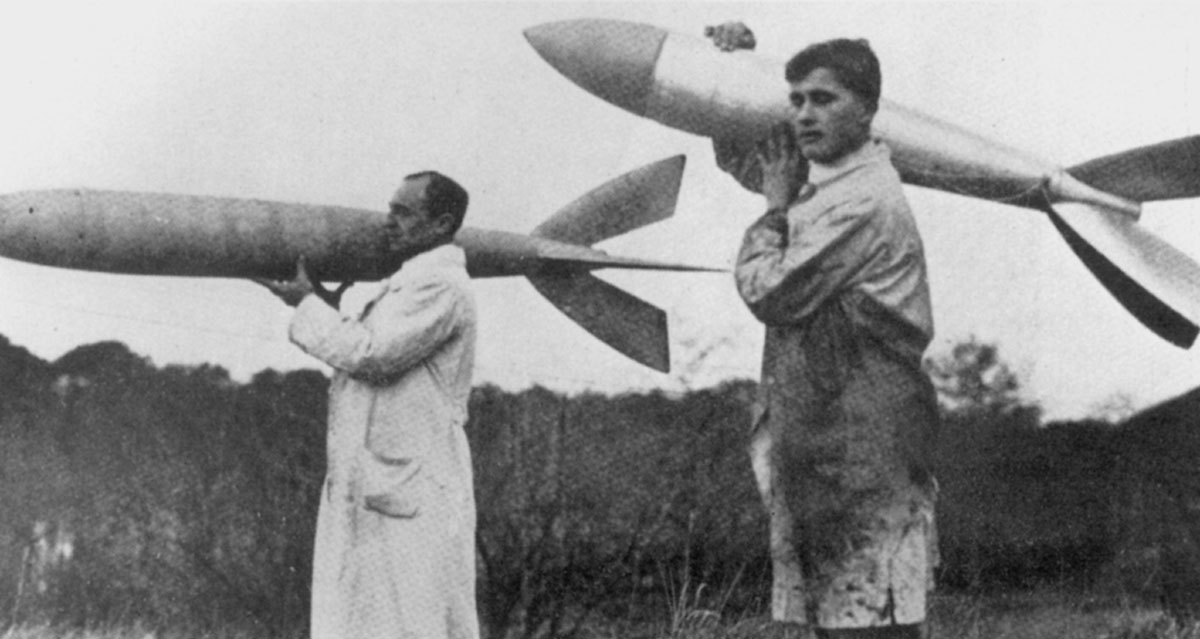

| |

| Boys and their hobbies. Wernher von Braun, at right, about 1932. |

Wernher von Braun realized early on that rockets ran on funding almost as much as they did on fuel. Since rockets were not considered an effective military weapon, the Treaty of Versailles did not restrict the production of ballistic missiles. This omission proved endlessly fascinating to the German Army, who hired von Braun and his cohorts at VfR to build ever-increasing numbers of military rockets.

The German Army ordered the von Braun team to create a rocket that would be able to carry a 100-kilogram explosive warhead a distance of 260 kilometers. Although too late to have an effect on the outcome of World War II, the von Braun A4 rocket (or V-2 as named by the Nazi hierarchy for “Reprisal Weapon-2”) delivered murderous damage to London and Antwerp at nearly four times the speed of sound. Rocket attacks from Germany killed more than 12,000 people and destroyed over 30,000 homes. Overlooked in the death toll are the fatalities of the 10,000 forced laborers and concentration camp inmates who worked on V-2 production at the Peenemünde and Nordhausen rocket facilities. Stationed in bombproof cave factories, many of the inmates died of pneumonia in the cold, damp working conditions.

Responsibility for these many deaths rested in no small part on the shoulders of von Braun and his staff. They realized their only hope in escaping war crimes charges would be in their ability to negotiate with the victors by trading technical information for their freedom.

The calculation was simple: if von Braun’s team surrendered to the Soviets, they'd face the wrath of a nation with 27 million war dead. The other choice was to bargain with the Americans, the fellow countrymen of rocket pioneer Robert Goddard. The von Braun team fled to the West, negotiating with their potential benefactors for a cave full of unused V-2 parts, milling machines, crates of technical documentation and engineering advice in exchange for political asylum. As the Germans had done back in the 1940's, the US Army put von Braun and his men to work, rebuilding V-2s and designing interregional ballastic missiles capable of carrying atomic bombs from border countries to downtown Moscow.

From the original V-2 came the Redstone and the Jupiter, suborbital missiles with more power than the original German model. In fact, it would take only a slight bit of tweaking (and funding) to get these new missiles to push a satellite into Earth orbit.

Once again, von Braun followed the research money to its source: in this case, the American taxpayers. Dr. von Braun’s public relations campaign had to move the popular culture away from the “mad scientist” stereotype imbued by earlier newspaper reporting of Robert Goddard’s Moon plans of the 1920s and replace those notions with the idea that space travel was not only practical, but imminent.

|

| Dr. von B's PR campaign. |

In 1952, Collier’s Magazine began publishing a series of articles written by von Braun and his colleagues, detailing the processes, potentials, and benefits of a manned space program. The magazine series, painstakingly illustrated with the cinematic realism of artist Chesley Bonestell, gave readers the impression that the government was already involved in building manned spacecraft, and that the only impediment to the conquest of space was additional government funding.

Dr. von Braun proved to be a master of Amercan public relations, eventually convincing Walt Disney to produce a series of TV features about "Man in Space" on Walt's "Disneyland" series. Millions of Americans watched the documentary-style programs, which reinforced the idea that America was on the threshold of conquering space.

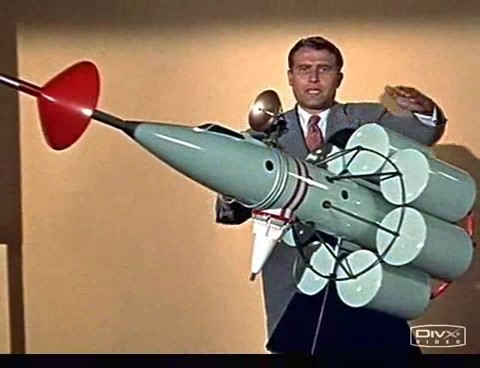

|

| "That's not my department, Walt," says Wernher von Braun. |

President Eisenhower requested a print of the Disney program to screen at the Pentagon. However, he still was reluctant to rely on an ex-Nazi to experiment with world-girdling missiles over the Soviet Union. Ike proposed that the United States would orbit a scientific satellite during the International Geophysical Year of 1957. To avoid any semblance of military legacy from the former V-2 engineers, the President also designated the Navy's untested rocket, Vanguard, as the launch platform for the first satellite.

The President's Technological Capabilities Panel laid down the law to the Department of the Army: von Braun's team would in no way be allowed to launch anything into orbit. To make sure of this, the Army dispatched inspectors to Cape Canaveral to make sure there were no extra stages laying around to attach to the top of any Redstone or Jupiter missiles. The configuration of the 4th stage of the Army's Jupiter-C missile was loaded with sand, as extra ballast to prevent an "accidental" satellite.

| |

| The Jupiter-C, with its inert fourth stage up on top. |

So, on September 20th, 1956, the US Army launched a four-stage Jupiter missile with an inert top stage. The payload of 30 lbs of sand flew to an altitude of 680 miles at 16,000 mph, only to land in the South Atlantic, having never orbited the Earth. If the sand had been aluminum perchlorate rocket propellant, the Space Age would have begun that day.

The person aided most by this nearly orbital flight was the guy who designed rockets for the Soviet Union: Sergei Korolev. The Soviet Chief Designer made the case to the State Commission that their own plodding space program would need to be streamlined and funded better to put a small, simple satellite into orbit before the Americans. Korolev received permission from the State Commission to concentrate on launching a 184-lb satellite code-named "Object PS" and later renamed Sputnik. Sputnik would achieve orbit 13 months after the Jupiter-C launch.

The US Navy tried to launch their Vanguard about two months after Sputnik went into orbit. It didn't go too well.

|

| Vanguard's peak altitude: 4 feet, followed by a lot of exploding and burning. |

After the Navy's very public failure, Eisenhower okayed von Braun's team to go ahead with an active fourth stage on their Jupiter missile, and a science satellite inside the nose of that top stage. Now renamed a Juno-I, the new launch vehicle hoisted the 30-lb payload into orbit on the last day of January, 1958. The Explorer 1 satellite was a success, sending back telemetry from high Earth orbit about a shell of radiation surrounding the planet. The shell, now called the Van Allen Belt, was named after a University of Iowa scientist who suggested putting a geiger counter inside the satellite.

America didn't get an actual spy satellite into orbit until the final weeks of the Eisenhower administration, but the resulting data told Ike (and select members of Congress) that there was no "bomber gap" with the Soviet Union. The Soviets didn't have much in the way of intercontinental military aircraft, so Congress didn't waste a lot of money building unnecessary anti-aircraft defense systems.

It's easy to be bothered by Eisenhower's intentional delay-of-game, but two benefits came from America being second into orbit. First, the Soviet launch of Sputnik confirmed their tacit approval of the Open Skies policy, at least with spaceships in Earth orbit. Second, without the Soviets getting into orbit first, there would have been no ensuing Space Race, and consequently no Race to the Moon. I think we should count our blessings and move on.

Terrific, Jim! You tell a good story. I bought a couple of those old Collier's magazines for my own research and they're pretty amazing (the two-page Bonestell spread in WHTTWOT is from a Collier's piece I scanned myself because Bonestell's official archivist didn't have a good enough version available). And any essay that works in a Tom Lehrer title is tops in my book.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Brian! This was one of those timely topics whose anniversary arrived a bit before I was ready to type. Some chunks of this screed may be destined for the Sekrit Rocket History Book, so it was a good ironing-out of a bunch of scrawled notes and text files.

ReplyDeleteAfter re-reading the Tolstoy-level spew, I really need to work on better thumb placement for the end of the rhetorical garden hose - - less fact-reeling and blah-blah-blah, more campfire stories and "A to B to C and back to A" stuff.